A piece I wrote back in 2016:

On May 25, 1911, Laura Nelson, her baby daughter and her teenaged son were kidnapped from a jail in Oklahoma by an angry mob. The two had been jailed for what, by all accounts, seemed to be the accidental death of a deputy sheriff during a scuffle at the Nelsons’ home where police were investigating the theft of a cow. Laura’s husband, her children’s father, pled guilty to the theft and had been taken to prison.

Laura and her son were awaiting trial in the jail when a group of between 12-40 men broke into the jail and took them out. Laura was reportedly raped by members of the mob, and some reports say that her son Lawrence was castrated, before both were hung from a bridge. A photograph shows 58 spectators on the bridge as the two bodies hang below, including 35 men, six women and 17 children. It is not known what became of Laura’s baby daughter, although at least one account says that she was taken in and cared for.

To think of this as “mob justice” defies reason. Laura and her son were awaiting justice – or what there was of it in early-20th-century Oklahoma – in jail. What was done to them was not the product of any kind of justice, but of blind hatred and a desire to “teach a lesson” to lesser (black) beings who dared commit any kind of crime against their white superiors. Like all such grotesque crimes, its purpose was to keep African Americans “in their place.”

According to the Tuskeegee Institute, 3,446 blacks and 1,297 whites were lynched in the years between 1882 and 1968. Anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells found that the most common accusation against black lynching victims was murder or attempted murder, while about 30% were accused of rape or attempted rape, with the remainder accused of everything from “… verbal and physical aggression, spirited business competition, (to) independence of mind.”

Given this horrifying legacy, it is understandable that black Americans today would be wary of any solutions to current problems with policing that might smack of vigilante justice. It is understandable that those of us who call, not for reform, but for an end to policing as we know it, run up against a wall of resistance from those whose only other point of reference is uncontrolled vigilante mobs.

And yet it is also clear that the current state of law enforcement in this country – especially for African Americans – has reached an unacceptable level of violence and abuse. More than one commentator has drawn the comparison between the lynchings from the past and what have now become routine murders by police officers of – often unarmed – black Americans.

Some explain away the discrepancy between black and white murders by police by pointing out that African Americans commit more crime than do other groups – as if there is some natural rate, correlated with crime rates, at which any group of people ought to be killed by those sworn to protect them. If such a natural rate does exist, then someone needs to tell police in other countries about it. Police in the UK for example are woefully below quota, having only killed around six of their citizens in the past five years, as compared to at least 1,000 per year in the US.

The fact remains that, in addition to boasting the largest prison population in the world, the US also lays claim to one of the most violent and militarizedforms of law enforcement – complete with chilling echoes of a past in which “uppity” behavior or “independence of mind” was cause for immediate execution.

Particularly in low-income communities, police have become more predators than protectors, seeing citizens not as their employers, but as a source of income, a means to fulfill arrest quotas, and increasingly, an enemy to be subdued.

While the US may be an extreme example of these ills, none of this should come as a surprise. In a monopoly system, devoid of competition and meaningful accountability, police and the prison system have perverse incentives: Not to prevent crime, but to arrest and imprison as many people as possible. Not to make neighborhoods safe, but to extort as much money from citizens as possible.

So what is the solution? Are we required to choose between the lesser of two evils: An abusive and unaccountable police state, where officers of the law are free to murder, steal, rape and assault with impunity – or a world of brutal and equally unaccountable lynch mobs? Are these the only options available to us?

Fortunately not.

It is worth remembering that policing as we know it is a relatively new phenomenon – in fact, police departments did not even exist in the US or England prior to the mid nineteenth century. And when they were created, it was not in response to any increase in crime, but as an attempt to more effectively control protesting crowds, striking workers and rioting slaves. So the prospect of not reforming, but eliminating, police departments is not as radical as it may sound.

In the absence of government police departments, would public safety be left in the hands of vigilantes? Would justice be dealt out by uncontrolled lynch mobs? There is no good reason to think so. In fact, historically lynch mobs have been enabled, not hindered, by local police departments.

Remember that the only reason those mobs were able to get away with their crimes was that the law was either explicitly or implicitly on their side. According to the book “Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880 – 1930”, “63% of all lynching victims were seized by mobs while in the custody of law officers.” And as Isabel Wilkerson writes in The Guardian:

“During formal Jim Crow, lynchers killed with impunity. Rarely was there so much as an inquiry. Sheriffs were often actively involved, in attendance or chose not to intercede.”

Imagine how different things might have been, had black Americans been able to have their own police forces, competing with and challenging white police forces. The idea is not new. Economists such as Murray Rothbard, David Friedman and others have outlined in painstaking detail how non-monopoly systems of protection and defense might work, and indeed how they have worked in the past.

As it happens, we don’t need to imagine it. There are already real-life examples of private companies and groups doing protection work that puts their statist counterparts to shame. One of the most notable is the Detroit Threat Management Center, a private company that has been making some of Detroit’s roughest neighborhoods safer for more than 20 years.

In an interview with Tom Woods, DTMC’s founder, Dale Brown tells how he cleaned up one of Detroit’s worst neighborhoods when the police wouldn’t.

Dubbed “Crack Alley”, the area consisted of about ten apartment buildings and, according to Brown, about 100 aggressors, making up about 25% of the population. “There were hundreds of people who needed help,” he says. “I couldn’t get the police to help them.”

So Brown went to the building owners and made them an offer: In exchange for one free apartment in a building, he would train and install one person to protect that building. Prior to his staff’s arrival, Brown says that there had been a home invasion every day, and murders every month. “From the day I started,” he says, “there was only one more home invasion – I caught them – and there were no more murders from the day I started.”

Brown calls his methods “a completely new paradigm in public safety:

“…building owners suddenly went into the black for the first time in 20 years, because no-one moved from the buildings and everyone paid their rent. All of a sudden, as a result of people paying their rent… these corner stores, liquor stores, laundromats, all the places started to flourish because they had more customers.”

“Wealthy people get wealthier when there is less death, carnage, lawsuits, injuries and incarcerations on their property… they like my peaceful approach because it means more prosperity for them. But my focal point was community and family safety.”

“It’s sustainable because it’s profitable,” says Brown. “Look at crimemapping.com – you will see an extremely low amount of crime anywhere that we work.”

Over the years, Brown’s methods have evolved to become more peaceful, less confrontational. It is an approach born of necessity. Unlike government police officers, Brown and his team have to behave in accordance with the law. As civilians, they know they will be held accountable for their actions – and that accountability has paid off, both for Brown and the DTMC, and for the neighborhoods they serve:

“(I’ve learned better ways of crime prevention) because I have to,” says Brown. “I’m accountable. I have no qualified immunity. That means, if I put my hands on someone it has to be legal. There has to be a way for me to explain it as a civilian. As a result, we’ve had no court date in 20 years. No lawsuits… in 20 years.”

The methods he uses are diametrically opposed to those used by the police:

“Think about everything you think about in terms of law enforcement and we do the exact opposite. So a police officer thinks you’re a threat, so what they do is pull you over. If we think you’re a threat, what we do is we pull up to you and talk to you. If a police officer thinks you’re a threat, what they do is stay back away from you and pull out their gun. What we do is get so close you can’t get pull out your gun. A police officer believes you’re a threat so they begin to talk to you in an autocratic, aggressive fashion. What we do is build a psychological bridge to explain to you that there is no need, there’s no option for violence, there’s no opportunity, and there’s nothing to gain. So you must leave now, and I’m letting you leave. My staff is letting you leave. You can simply go.”

“Now this works in any situation where the human being is attempting to achieve something. Now when it’s psychological, meaning the person is not thinking well, they’re on drugs or they’re in pain… we’re able to read their body language ahead of time, and know that they’re about to draw their weapon… …we’re able to take them into custody and take them down without injuring them and without letting them pull out their gun.”

“Again, we’re in Detroit. This is not theory. This is what we do. This is why none of my staff members are dead.”

The biggest differences between DTMC and government police? Accountability – by virtue of the fact that DTMC staff are not above the law – and the fact that they do not prosecute victimless “crimes”. “We don’t get involved in drugs and other issues that are non-violent,” says Brown. “We focus on just violence.”

Any attempt to reform our current system of policing will fail if it does not address the fundamental lack of accountability that is inherent in a monopoly system. It is time to start talking, not about “reforming” a fundamentally flawed system, but about abandoning it altogether.

Incentives matter. When people know that they will be held accountable for the violence they do to another person, they have an incentive to minimize that violence – as the Detroit Threat Management Center’s example illustrates so well. When people know that they will not be held accountable for their violence – as most police in America are not – that incentive to minimize violence is gone.

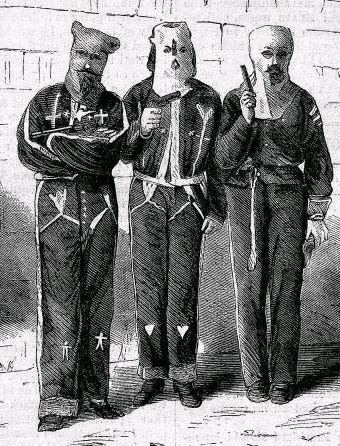

The people who participated in lynch mobs a hundred years ago knew that they would not be held accountable for their actions. They knew that they had the implicit support of law enforcement. That is why they were willing to stand at the scenes of their crimes and have their photographs taken with the bodies of their victims.

Lynch mobs are not what happen in the absence of a monopoly state – they are a symptom of the monopoly state. They are what happen when law enforcement is not held accountable by any competing agencies, and can choose which crimes to ignore. They are what happen when individuals are prohibited from forming their own organizations to defend themselves against those sanctioned by the state.

Indeed, presenting the choice between lynch mobs and the police state is more than just a false dichotomy: The one is the product of the other. The lynch mob could only ever arise in any meaningful way in a world where law enforcement is protected by its monopoly privilege – and can extend that privilege to the thugs of its preference. So no – we do not need to choose between vigilante mob justice and an abusive monopoly police state. We need to reject both.

how do we deal with the issue of incarceration? no doubt community patrols work. but if i own the jail and i send my thugs for the guy next door because i don't like him?

which is not to say that the government hasn't been doing that for the last 150 years...

Interesting concept. I could see it being highly effective for dealing with individual criminals, but I'm not clear on how it would work for dealing with large groups, like riots and vigilante mobs (which I could see still existing even under this system). I wonder what DTMC's track record is on that.