Porco Rosso: Anarcho-Capitalist Pig?

Originally published on LewRockwell.com, December 9, 2008

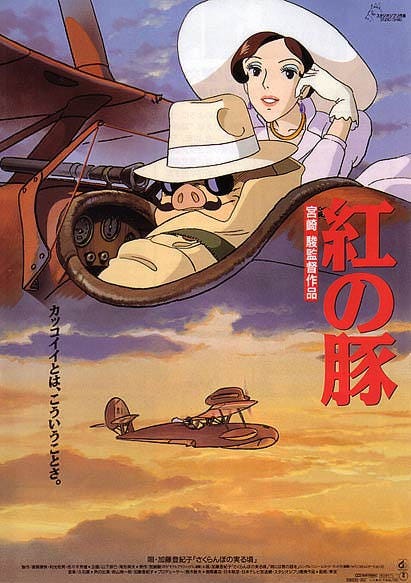

"This motion picture is set over the Mediterranean Sea in an age when seaplanes ruled the waves. It tells the story of a valiant pig, who fought against flying pirates, for his pride, for his lover, and for his fortune. The name of the hero of our story is Crimson Pig."

Like more and more families these days, ours does not have TV. We do watch movies, and even TV shows that we get from Netflix, but these are mostly for my husband and myself. We don't want our 22-month-old son to spend his childhood in passive receptivity of all that mainstream media has to offer (and to his credit, he's usually more interested in dismantling the remote anyway). He knows nothing of Barney or Dora the Explorer, and it is my fervent hope that he never learns about Sesame Street.

I do make a few exceptions though, and one of them is for Hayao Miyazaki. For anyone who is not familiar with this man, he is quite simply the greatest living director of animated film. He is also one of the greatest filmmakers, and I would even argue one of the greatest artists, of our time. The creator of such works as "My Neighbor Totoro," "Kiki's Delivery Service" and his masterpiece "Spirited Away" puts American children’s filmmakers to shame with works of breathtaking beauty, imagination and stories and characters that respect the intelligence of children.

In Miyazaki's films, there is no attempt to "mold" my child's character; no trying to "teach him a lesson," make him a better person or help him grow up to make the world a better place. There are values if you look for them, but essentially these films are just plain fun. One of my favorites is Porco Rosso. The story's hero is a freelance bounty hunter who flies his bright red airplane around the Mediterranean hunting down air pirates for cash. And yes, he is a pig. The film is great fun, there are scenes that will literally take your breath away, and the drama is as sophisticated as that of many adult films. But there's something else. Around my third or fourth viewing, it dawned on me that Porco Rosso is an anarcho-capitalist!

Mid-way into the film, we learn that Porco is wanted by the Italian government. There are warrants out on him for "treason, illegal entry, decadence, pornography and being a lazy pig." His former fighting buddy begs him to come back to the air force where he had once been a hero. "I could still get you in," he tells Porco.

Porco responds "better a pig than a fascist."

"Freelance daredevils are finished," says his buddy. "To fly now you need a government or an airline to pay you."

"I only fly on what I earn myself" Porco replies.

As his friend gives up on bringing Porco back into the fold, he warns him: "be careful. They won't bother with a court of law." And indeed, Porco spends the rest of the film hotly pursued by the fascist secret police.

Of course the exchange begs the question: If the government wants to throw Porco in jail, and if he only flies on what he earns himself, then who is it who is paying him to be a bounty hunter? Clearly it must be the shipping companies themselves. This suspicion is given further support when we see one of the luxury liners with its own fleet of fighter planes trying to fight off a band of pirates.

It seems clear that Porco is operating in a world where private agents — even those who are themselves on the run from the law — are free to contract their protection services out to other private agents. Maybe there is a message to this film after all.

What a far cry from our own world, where Somali pirate attacks have become nearly daily news items. While some private firms are beginning to offer their services as guns for hire on the high seas, many nations prohibit the carrying of arms aboard ships that carry their flags, effectively disarming shippers and creating floating buffets for the pirates. Porco would sneer at this.

But then Porco Rosso is the quintessential rugged individual; a lone, solitary pig. When he makes a large cash withdrawal from the bank, the teller asks him if he wants to make a contribution "to the people" with a Patriot Bond.

"I'm not a person," is Porco's terse reply.

Later, when his arms merchant warns him that the government may pass laws against what he does, he replies "laws don't apply to pigs." (After Porco leaves, the merchant's son asks "how's war different from bounty hunting?" His father replies "war profiteers are villains. Bounty hunters are just stupid.")

He even smokes (yes, in a children's film!), drinks, and has sexist attitudes — although that doesn't stop him from hiring the plucky young heroine Fio to rebuild his airplane. But he is also a good friend, true to his word and devoted to his childhood sweetheart. In the end, we are charmed by him, a little envious of his freedom to fly around the Mediterranean as he pleases, and a little sad for him in his solitude — all things you'd hope for in a good adult movie with real live actors (instead of drawings of a pig).

"Porco Rosso" is not unique among Miyazaki's work in this regard. Adults will find his films as engaging and enjoyable as (and in some cases more than) children will. And while some may be turned off by the environmentalist themes of "Princess Mononoke" and "Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind" (personally, I've never been one to equate concern for the environment with support for statist intervention, but that's just me) they should not let this stop them from enjoying such films as "My Neighbor Totoro," "Kiki's Delivery Service," "Howl's Moving Castle," and of course "Spirited Away." Each of these films is wonderfully crafted and unique. And if there is a message to any of them, it is a message about self-reliance, loyalty, believing in oneself and the value of hard work. Entrepreneurs frequently feature as heroes, for instance in "Kiki's Delivery Service" where a young witch seeks her fortune in a new city by starting a broomstick-powered delivery service. In "Spirited Away," the heroine Chihiro is transformed through hard work and taking on responsibility.

As much as it is a relief to watch children's films that portray doing business, being independent and earning money in a positive light, it is even more of a relief to find an entire selection of children's films that are not aimed at manipulating children. For as well-intentioned as all those films about making the world a better place may be, they miss out on a fundamental truth both about filmmaking and about childhood: both are good in and of themselves. They do not need some external purpose to make them worthwhile, or some outside agenda to make them more meaningful. And perhaps the secret to Hayao Miyazaki's success is that he understands this simple truth. Because he has given us films about flying pigs, enchanted bath houses and magical woodland creatures, the world is already a better place.